Every year, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. Yet, many doctors still hesitate to prescribe them - not because they doubt their effectiveness, but because they’re not sure they understand them well enough. That’s the real problem: continuing education for doctors on generics isn’t consistent, clear, or always relevant to their daily practice.

Why Generics Matter More Than Ever

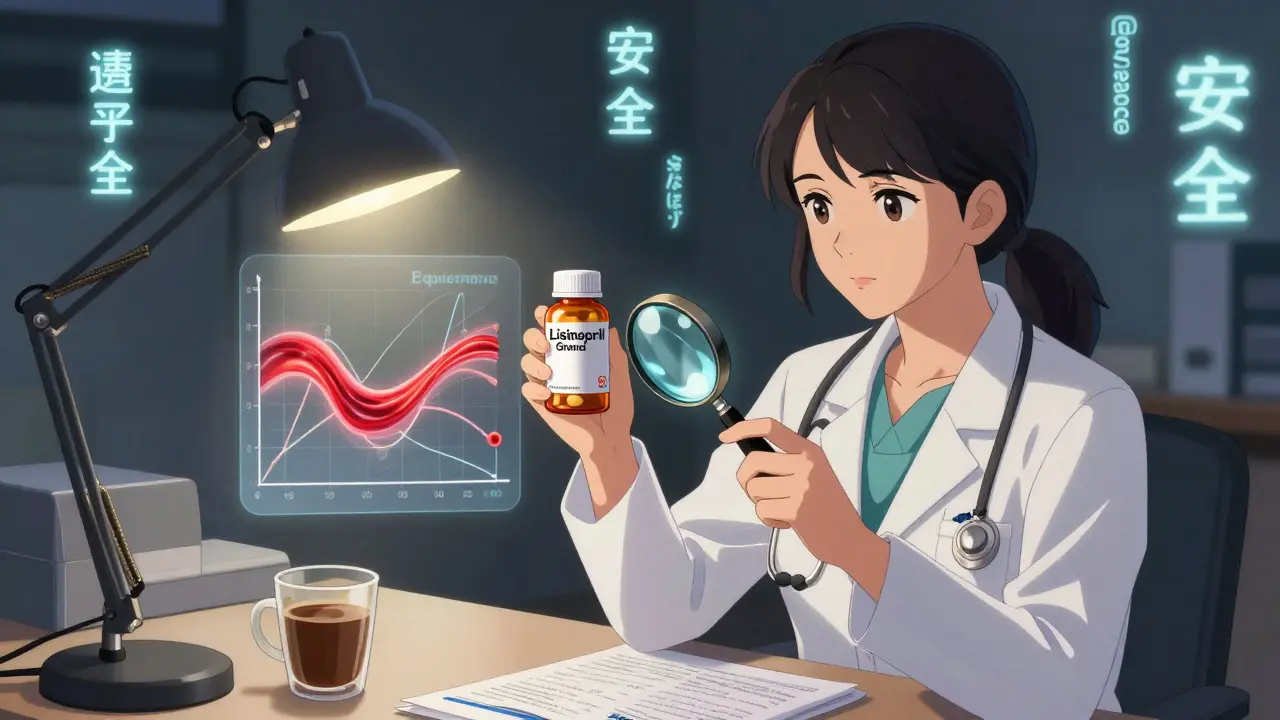

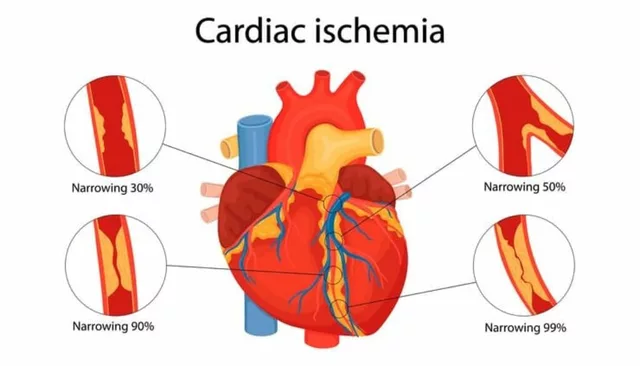

Generic drugs aren’t cheap knockoffs. They’re exact copies, approved by the FDA to work the same way as brand-name drugs. The FDA requires them to have the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They must also be bioequivalent - meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at the same rate. In real-world terms, that means a patient taking a generic version of lisinopril will get the same blood pressure control as if they took the brand-name version. The numbers don’t lie. Generics make up 90.7% of all prescriptions but only 22.9% of total drug spending. That’s a $156 billion annual savings potential, according to the RAND Corporation. For patients on fixed incomes, chronic conditions, or multiple medications, switching to generics can mean the difference between adherence and abandonment. But here’s the catch: doctors need to know when and how to switch. Not all generics are created equal in every situation. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin - even tiny differences in absorption can matter. That’s why education isn’t optional. It’s essential.What CME Requirements Actually Look Like

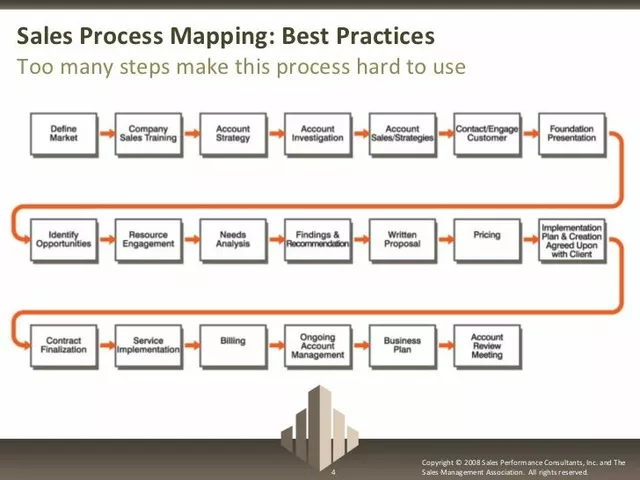

There’s no national standard for continuing medical education (CME) on generics. It’s a patchwork. Forty states require between 20 and 50 hours of CME every two years. Ten states have no mandatory requirements at all. California demands 50 hours of Category 1 CME every two years, but doesn’t specify how much must be pharmacology-related. Maryland requires three hours of CME on opioid prescribing - with half an hour dedicated to Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. Georgia wants 40 hours total, with 10 of those focused on Category 1 credits, and an extra three hours on opioid prescribing for DEA-registered doctors. The real shift came with the MATE Act in June 2023. Now, every doctor with a DEA registration - that’s most prescribers - must complete eight hours of training on substance use disorders. This includes education on generic alternatives to controlled substances. Compliance is mandatory by June 2025. And it’s not just opioids. California updated its rules in January 2024 to require two hours of training on biosimilars - complex, biologic generics that are harder to replicate than traditional pills. These aren’t just policy changes. They’re responses to real clinical needs.What Doctors Actually Learn - and What They Miss

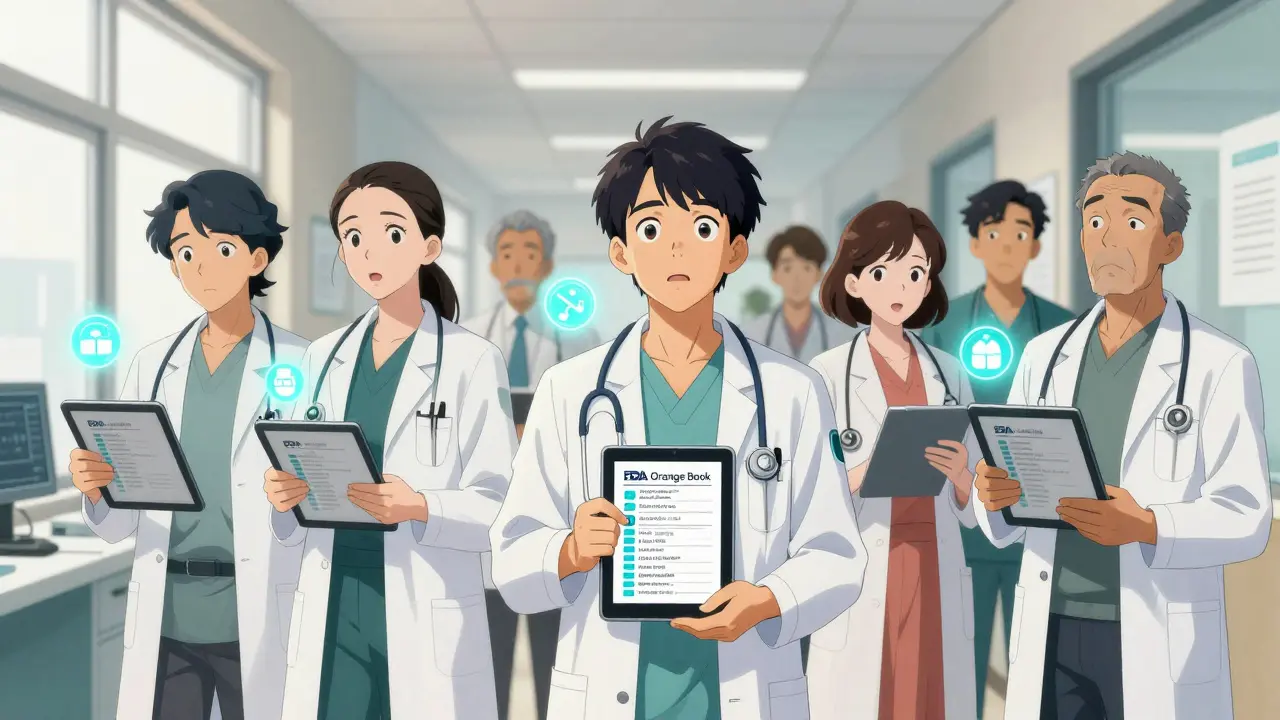

Most CME courses on pharmacology cover the basics: how to read the FDA’s Orange Book, how to identify therapeutic equivalence codes, and how to explain bioequivalence to patients. Courses from accredited providers like UpToDate, Medscape, and RenewNowCE include learning objectives like “distinguish generic from brand names” and “identify common drug interactions.” One study found that doctors who completed pharmacology-focused CME improved their generic substitution decisions by 17.3%. Another showed that when doctors understood generics better, patient concerns dropped by 40%. Dr. Emily Rodriguez, a family physician in California, says her patients stopped asking, “Is this the real drug?” after she walked them through the FDA’s approval process. But not everyone finds it useful. A survey on the Sermo physician network showed that 32% of doctors felt the content was irrelevant to their specialty. A radiologist told the forum, “I prescribe contrast agents, not painkillers. Why am I sitting through 12 hours on opioids?” That’s the flaw in the system. CME is often one-size-fits-all. A dermatologist gets the same pharmacology module as a cardiologist. A psychiatrist gets the same opioid training as a primary care doctor who rarely sees addicts.

Where the System Falls Short

The biggest problem isn’t lack of content - it’s lack of context. Most CME modules are passive: watch a video, take a quiz, get credit. There’s little connection to real-time decision-making. Doctors aren’t learning how to use the Orange Book during a busy clinic day. They’re not learning how to quickly compare generic alternatives in their EHR system. They’re not learning how to respond when a patient says, “My cousin took this generic and it didn’t work.” That’s why adoption is low. A 2022 study in Academic Medicine found that physicians completed only 68.4% of required pharmacology CME modules - compared to 87.2% for clinical topics like diabetes or hypertension. Why? Because pharmacology feels abstract. It doesn’t feel urgent. The solution? Integration. Sixty-three percent of doctors now use CME tools that plug into their EHR. UpToDate, for example, gives 0.5 CME credits just for reviewing a drug monograph while looking up a patient’s medication. That’s learning on the job - not in a webinar.What Doctors Need to Know Now

You don’t need to memorize every generic name. But you do need to know three things:- Therapeutic equivalence: The FDA assigns codes (like AB1, AB2) in the Orange Book. AB-rated generics are interchangeable. Non-AB-rated aren’t - and you need to know why.

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs: For drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or cyclosporine, stick to the same manufacturer unless you’re monitoring levels closely. Switching brands here can be risky.

- Biosimilars: These aren’t traditional generics. They’re complex biologics. The FDA approves them based on clinical data, not just chemical equivalence. Don’t assume they’re interchangeable without checking the label.

The Future Is Personalized

The next big shift won’t be more hours. It’ll be smarter learning. The National Academy of Medicine is piloting competency-based assessments in 12 states. Instead of checking a box for 50 hours, doctors will prove they can correctly choose generics for specific patient scenarios. AI-driven platforms are already emerging. McKinsey predicts that by 2027, CME will adapt to your prescribing habits. If you prescribe a lot of statins, the system will push you new generic options for atorvastatin. If you rarely touch opioids, you won’t be forced to sit through 12 hours on pain management. This isn’t science fiction. It’s the next step in making CME useful again.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t have to wait for your state to change its rules. Here’s what you can do right now:- Check your state’s medical board website for current CME requirements. Don’t assume - rules change every year.

- Find one free, accredited pharmacology course. Start with the FDA’s Orange Book primer or ASHP’s modules.

- Use your EHR. If your system links to UpToDate or Micromedex, spend five minutes reviewing a drug you’re about to prescribe. You’ll earn CME credits while you work.

- Ask your pharmacist. They know which generics are actually being dispensed, which ones have supply issues, and which ones patients report problems with.

- Start a conversation with your patients. “This generic is FDA-approved to work just like the brand. It’s cheaper, and studies show it’s just as effective.” You’ll build trust - and reduce non-adherence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to be bioequivalent to their brand-name counterparts - meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. Studies show no difference in clinical outcomes for most drugs. For 90% of prescriptions, generics work just as well.

Why do some patients say generics don’t work for them?

Sometimes, it’s about expectations. Patients who’ve been on a brand-name drug for years may believe the generic is inferior. Other times, it’s the inactive ingredients - fillers or dyes - that cause minor side effects. Rarely, for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, switching manufacturers can cause slight changes in absorption. That’s why consistency matters for those specific drugs.

Do I need to re-educate myself if I’m not a prescriber?

If you’re a physician with a DEA number - even if you don’t prescribe opioids - you’re required to complete the MATE Act training. If you’re not a prescriber, you still benefit from understanding generics. You’ll better support patients, reduce unnecessary costs, and avoid misinformation in your practice.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are chemically identical copies of small-molecule drugs - like pills. Biosimilars are copies of complex biologic drugs - like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis treatments. They’re not exact copies because biologics are made from living cells. The FDA approves them based on clinical data showing they’re highly similar, with no meaningful differences in safety or effectiveness.

How do I know if a generic is AB-rated?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book, available free online. Drugs with an AB rating are considered therapeutically equivalent and interchangeable. If a drug has an AB1, AB2, etc., it’s interchangeable with the brand. If it’s listed as “NR” (not rated), it’s not considered interchangeable.

Is CME on generics mandatory everywhere?

No. Only 42 states require physicians to demonstrate knowledge of generic vs. brand-name drug identification as part of CME. But the MATE Act now requires eight hours of substance use education - including generics - for all DEA-registered practitioners. That covers most prescribers nationwide.

David Chase

December 30, 2025 AT 01:41