When you take a pill for a serious condition like epilepsy, heart failure, or organ transplant rejection, you expect it to work the same way every time. But if that pill is a narrow therapeutic index drug, even a tiny change in how your body absorbs it can mean the difference between healing and hospitalization. That’s why regulators don’t treat these drugs like ordinary generics. They’ve built special rules - stricter, smarter, and more precise - to make sure every generic version performs exactly like the brand-name original.

What Makes a Drug a Narrow Therapeutic Index Drug?

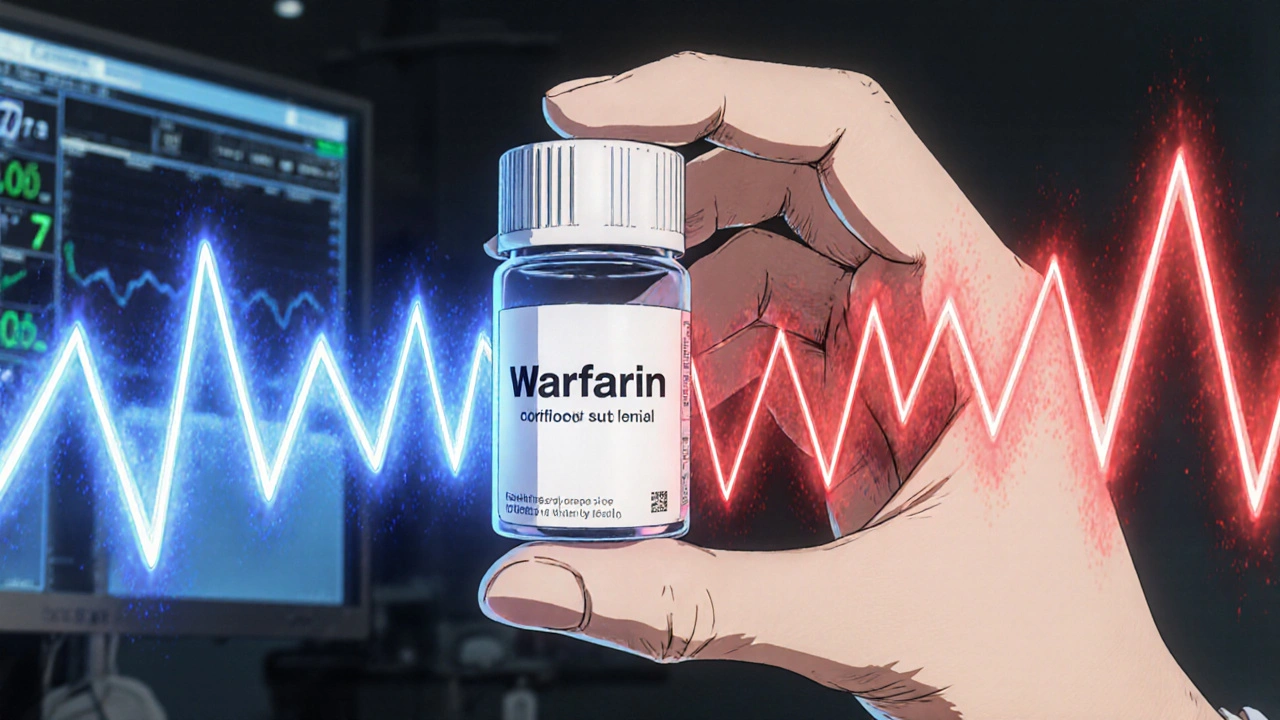

A narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug is one where the gap between a safe dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. Think of it like walking a tightrope: too little, and the treatment fails; too much, and you risk severe side effects - even death. The FDA uses a therapeutic index of 3 or less as the cutoff. That means the dose that causes harm is only three times higher than the dose that works. For most drugs, that ratio is 10, 20, or even 100. For NTI drugs, it’s not even close. Common examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid disorders), digoxin (for heart rhythm), phenytoin (for seizures), and tacrolimus (to prevent organ rejection). These aren’t optional medications. They’re life-sustaining. A 10% drop in blood levels of warfarin might lead to a clot. A 10% spike could cause dangerous bleeding. There’s no room for error.Why Standard Bioequivalence Rules Don’t Cut It

For most generic drugs, regulators accept bioequivalence if the generic’s blood levels fall within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s a 45% window - wide enough to account for normal variation in how people absorb medicine. But for NTI drugs, that window is too big. A generic that delivers 120% of the brand’s concentration might be perfectly safe for an antibiotic. For levothyroxine, it could trigger heart palpitations, bone loss, or anxiety. That’s why agencies like the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada had to rethink the rules. In the 1970s and 80s, doctors started noticing that patients switching from brand to generic NTI drugs sometimes had unexpected side effects or treatment failures. Therapeutic drug monitoring - regularly checking blood levels - became common. But it’s expensive, invasive, and not practical for long-term use. So regulators turned to science: they needed a way to predict real-world safety without testing every patient.How the FDA’s Approach Works

The FDA’s current framework for NTI drugs, formalized in draft guidance from 2021 and expected to become final in 2024, is the most detailed in the world. To get approval, a generic must pass three tests:- Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE): This adjusts the acceptable range based on how variable the original drug is in people. If the brand drug’s levels swing a lot from person to person, the generic can too - but only up to a point. This is smart because it doesn’t punish drugs that naturally vary.

- Variability Comparison: The generic’s variability can’t be higher than 2.5 times the brand’s. If the brand stays steady, the generic must be even steadier. This prevents manufacturers from using cheaper, less consistent formulations.

- Unscaled Average Bioequivalence: Even with the scaled limits, the average blood levels of the generic still need to fall within the traditional 80-125% range. It’s a double safety net.

How Other Regulators Compare

The FDA isn’t alone, but it’s the most complex. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) takes a simpler route: it applies a fixed 90-111% range for NTI drugs. No scaling. No variability tests. Just a tighter window. Health Canada uses 90.0-112.0% for the area under the curve (AUC), a key measure of drug exposure. The difference matters. The FDA’s approach is more scientifically precise but requires bigger, more expensive studies - often 36 to 54 patients instead of 24 to 36. That pushes costs from $300,000 to over $1 million per drug. The EMA’s fixed limits are easier to test but might miss subtle differences in variability that could affect long-term safety. Some experts, like Dr. Leslie Benet from UCSF, call the FDA’s method a “scientifically sound” breakthrough. Others, like Dr. Lawrence Lesko, worry it’s overkill. “Are we blocking generics just because we’re afraid of change?” he asked in a 2022 commentary. His point: not all NTI drugs behave the same. A drug with low variability might not need such strict rules.The Real-World Impact: Safety, Cost, and Access

NTI drugs make up about $45 billion in U.S. sales annually, according to IQVIA. But generic adoption lags. Only 68% of prescriptions for these drugs are filled with generics - compared to 90% for regular drugs. Why? Fear. Many doctors still prefer the brand, even if the generic is approved. Some patients report feeling different after switching, even when blood tests show no change. But real-world data tells a different story. A 2019 study in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes tracked over 10,000 patients on generic warfarin. No increase in strokes, clots, or bleeding. Just the same outcomes - at a fraction of the cost. The cost barrier is real. A single NTI bioequivalence study can cost twice as much as a standard one. That discourages small manufacturers from entering the market. And when fewer companies compete, prices stay higher - even for generics.

What’s Next? Harmonization and Better Classification

Right now, the FDA doesn’t have a single official list of NTI drugs. It decides case by case, based on guidance documents. That creates confusion for manufacturers. In July 2023, the FDA announced it’s building a new system - one based on quantitative therapeutic index calculations, not just expert opinion. That means more transparency. More consistency. More drugs might qualify. Industry analysts predict that by 2026, global regulators could align on a single set of standards. If the FDA’s RSABE model becomes the global norm, it could reduce study costs by 15-20%, according to McKinsey & Company. That’s good news for patients: more generic options, lower prices, and the same safety.What Patients Should Know

If you’re on a drug like levothyroxine, digoxin, or warfarin, don’t panic if your pharmacy switches to a generic. Approved generics under these strict rules are safe. But do this:- Keep taking your medication exactly as prescribed.

- Don’t switch brands or generics without talking to your doctor.

- Report any new symptoms - even small ones - to your provider.

- Ask if your drug is classified as NTI. If you’re unsure, look up the drug name with “FDA bioequivalence guidance” in a search engine.

What drugs are considered narrow therapeutic index drugs?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, levothyroxine, digoxin, phenytoin, tacrolimus, lithium carbonate, carbamazepine, theophylline, and sirolimus. These are used for conditions like blood clotting, thyroid disorders, heart rhythm, seizures, and organ transplant rejection. The FDA doesn’t publish a full official list but issues specific bioequivalence guidance for about 15 NTI drugs as of 2023.

Why are bioequivalence limits tighter for NTI drugs?

Because even small changes in blood concentration can cause serious harm - like seizures, organ rejection, or life-threatening bleeding. Standard bioequivalence limits (80-125%) are too wide for these drugs. Tighter limits, like 90-111% or the FDA’s reference-scaled approach, reduce the risk of therapeutic failure or toxicity when switching to a generic.

Are generic NTI drugs safe?

Yes - if they’ve passed the stricter regulatory tests. Real-world studies show no increase in adverse events for approved generic versions of warfarin, tacrolimus, and levothyroxine. The key is that these generics must meet exacting bioequivalence standards. Avoid switching between different generic brands without medical supervision, even if they’re all approved.

Why do some doctors still avoid prescribing generic NTI drugs?

Historical concerns and anecdotal reports from the 1990s and early 2000s created lasting caution. Some patients reported feeling different after switching, even when blood levels were normal. Today’s stricter standards have addressed those issues, but old habits persist. Education and real-world evidence are slowly changing minds. Many guidelines now support generic use when bioequivalence is confirmed.

How do I know if my drug is an NTI drug?

Check the drug’s prescribing information or search online for “[drug name] FDA narrow therapeutic index.” If the FDA has issued specific bioequivalence guidance for it, it’s classified as NTI. Common examples include levothyroxine, warfarin, and digoxin. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or doctor - they can check the FDA’s product-specific guidance documents.

Will generic NTI drugs get cheaper soon?

Potentially. If global regulators align on a single bioequivalence standard by 2026, manufacturers won’t need to run separate studies for each country. That could cut development costs by 15-20%, encouraging more companies to enter the market. More competition usually means lower prices. But until then, high study costs keep prices higher than for regular generics.

Henrik Stacke

November 21, 2025 AT 15:23