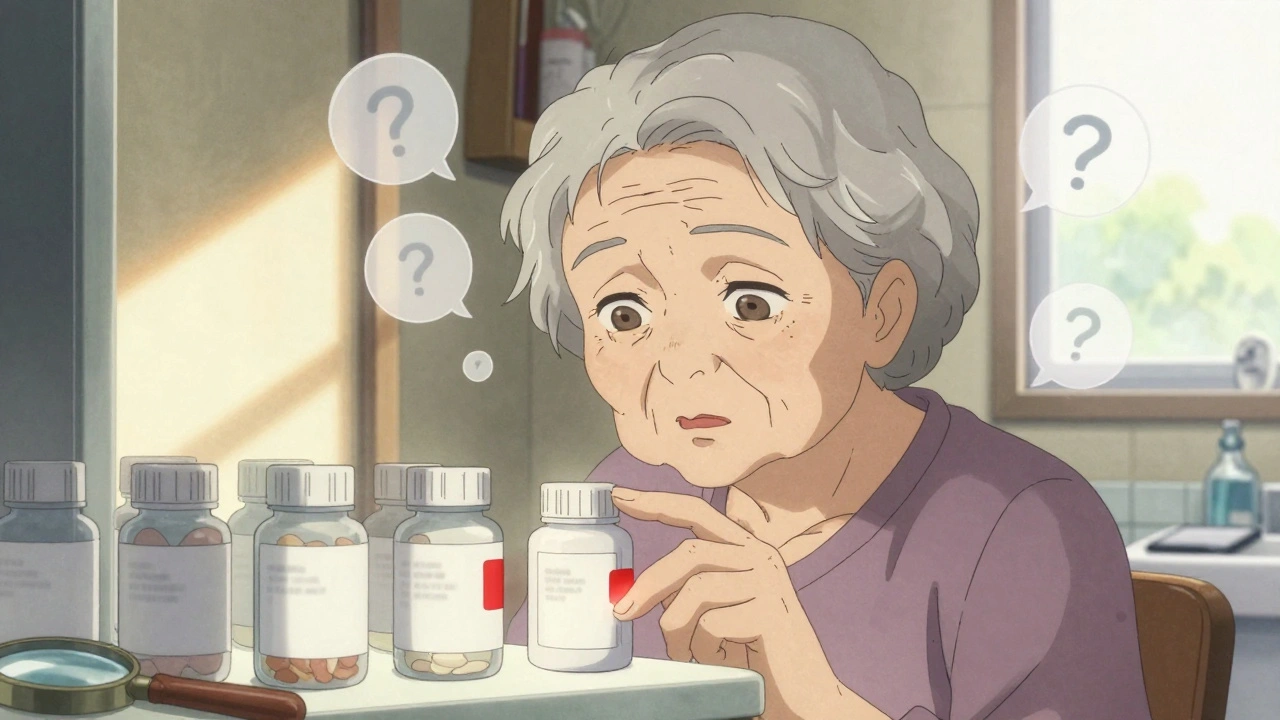

Imagine opening your medicine cabinet and not being able to tell which pill is which. All the bottles look the same-white, oval, no clear markings. You’ve taken this one before, you think. But was it the blood pressure pill or the sleeping pill? You can’t read the label. The pharmacist didn’t explain it clearly. And now, you’re guessing.

This isn’t rare. It’s happening every day to millions of people with low vision or hearing loss. In the U.S. alone, over 7.6 million people have significant vision impairment. In the UK, it’s 1.8 million. And for many, medication errors aren’t just inconvenient-they’re life-threatening. Studies show people with low vision are nearly 70% more likely to take the wrong dose or the wrong medicine than those with full sight. The problem isn’t that they’re careless. It’s that the system wasn’t built for them.

Why Standard Labels Fail

Most prescription labels are designed for people with perfect vision. Text is tiny-often 7 to 10 point font. The background is white, the ink is gray. There’s no contrast. No bolding. No clear separation between drug name, dosage, and instructions. For someone with low vision, this is unreadable. Even if they use magnifiers, the details blur together. Colors mean nothing if you can’t see them. A red pill and a green pill look identical if you have macular degeneration or glaucoma.

For people with hearing loss, the problem is different but just as dangerous. Pharmacists often give verbal instructions-‘Take this with food,’ ‘Don’t drink alcohol,’ ‘Call if you feel dizzy.’ If you can’t hear it, you miss it. Pharmacies are noisy. Background chatter, ringing phones, machines humming. Even with hearing aids, understanding speech in that environment is hard. And if you’re deaf or hard of hearing, you’re left with a paper slip and no way to confirm what the pharmacist said.

And it’s not just labels. Measuring liquid medicine? That’s a nightmare. A syringe with tiny markings? Impossible to read without perfect vision. Eye drops? You have to hold the bottle just right, and if you can’t see the tip, you risk contamination-or missing the eye entirely. A 2019 study found that only 39% of people with low vision could reliably use eye or ear drops without help.

What Works: Low-Tech Solutions That Actually Help

You don’t need fancy gadgets to make medication safe. Simple, low-cost changes make a huge difference-if they’re done right.

- Color-coding by time of day: Use colored tape or stickers on bottles. Red for morning, blue for evening, green for night. This works for 78% of users who try it, according to pharmacist surveys. Just make sure the colors are bold and high-contrast. Avoid pastels. Use black marker to write ‘AM’ or ‘PM’ directly on the bottle.

- Rubber bands: Wrap one band around a bottle for once-daily meds, two for twice-daily, three for three times. It’s cheap, fast, and doesn’t require reading. But here’s the catch: it only works if the person knows the system. If a family member sets it up and then isn’t around, confusion follows. Use this as a backup, not the only system.

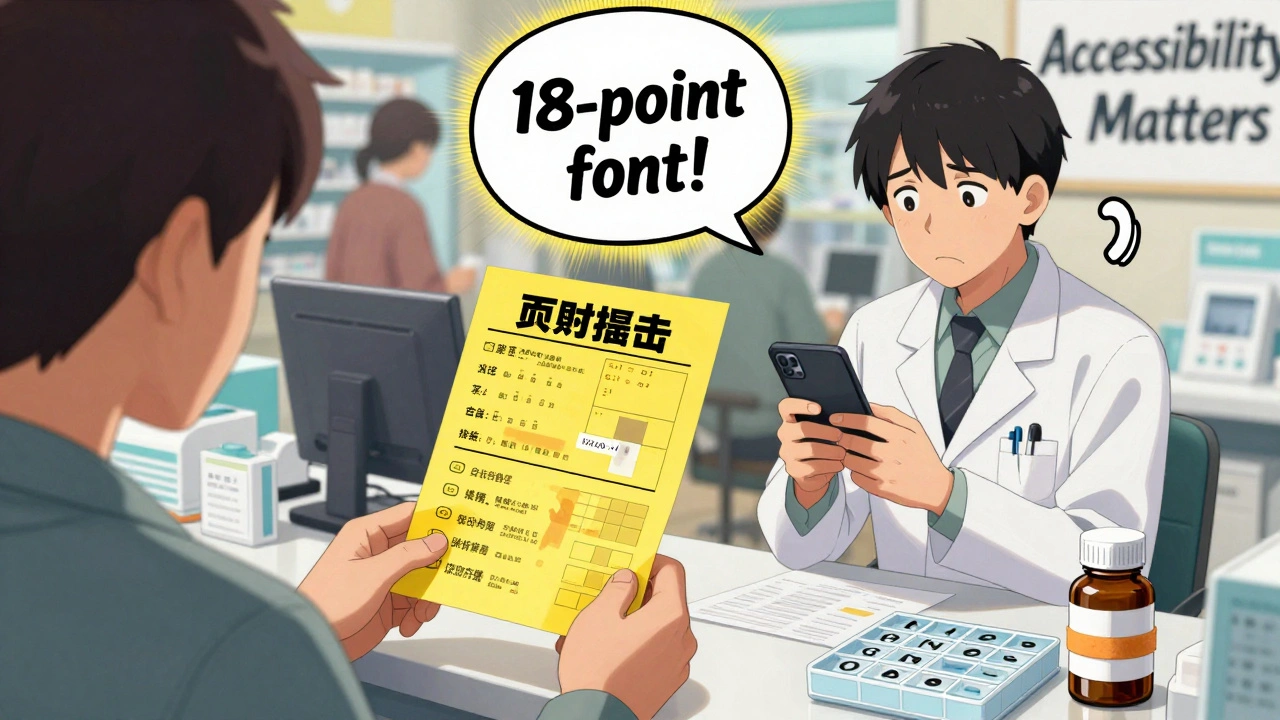

- High-contrast labels: If you’re printing your own labels, use black text on a bright yellow or white background. Font size? At least 18-point. No cursive. No italics. No tiny symbols. The American Foundation for the Blind says this is the minimum standard. Most pharmacies don’t follow it.

- Separate containers: Use pill boxes with labeled compartments. Buy ones with large print or tactile markings. Don’t rely on color alone-some people can’t see color differences. Use Braille if you know it. But here’s the reality: only 15% of adults who lose vision later in life read Braille. So don’t assume it’s useful.

One woman in Brisbane told me she keeps her pills in a muffin tin. Each cup is a time of day. She puts a rubber band around the tin to remind her it’s sorted. She doesn’t need to read a label. She just opens the cup. Simple. Effective. And it cost her nothing.

Electronic Tools: Helpful, But Not Perfect

Technology can fill the gaps-but only if it’s designed well.

The Talking Rx device, developed by a pharmacist in 2012, lets you record up to 60 seconds of audio for each pill. You press a button, and it says: ‘This is metoprolol, 25 mg, take in the morning.’ It’s been tested on 150 users. 92% improved adherence. But it costs $100 or more. Not everyone can afford it.

Apps like PillDrill or Hero Health use smart dispensers that beep, flash lights, and send alerts to phones. They can even notify a family member if you miss a dose. But they require a smartphone, internet, and the ability to set them up. For someone with low vision, that’s not easy. Screen readers don’t always work with these apps. Buttons are too small. Menus are confusing.

And here’s the big problem: these tools are not standardized. A pharmacy in Sydney might offer one device. A pharmacy in Melbourne might offer another. Your doctor doesn’t know which ones work. Insurance doesn’t cover them. Medicare pays pharmacies $14.97 per prescription. No extra money for accessibility. So most don’t bother.

What Pharmacies Should Be Doing

Pharmacists are on the front lines. They’re the last people to interact with you before you take your medicine. Yet only 28% of U.S. pharmacies spend the extra 3 to 5 minutes needed to properly label and explain meds to someone with low vision or hearing loss. Only 12% follow the full AFB labeling guidelines.

Here’s what they should do:

- Always offer large-print labels. Not ‘if requested.’ Offer them. Every time.

- Use tactile markers on bottles-raised dots for dosage, ridges for frequency.

- Ask: ‘Can you read this label?’ Not ‘Do you need help?’ That puts the burden on the patient.

- For hearing loss: write instructions. Use a tablet to show pictures. Use a video relay service. Don’t just shout over the counter.

- Train staff. Not just ‘be nice.’ Teach them how vision loss affects daily tasks. Teach them how hearing aids work in noisy rooms.

One pharmacy chain in Australia started training all staff on sensory accessibility in 2023. They now have a checklist: label size, contrast, audio options, tactile cues. They saw a 40% drop in medication error calls from patients in six months.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for the system to fix itself. Here’s what you can do today:

- Ask for large-print labels. Say: ‘I have low vision. Can you print the label in 18-point font with high contrast?’ Don’t apologize for asking.

- Bring a magnifier or phone with zoom. Use it to check labels at the pharmacy. If you can’t read it, say so.

- Use a pill organizer. Buy one with large print and separate compartments. Label it yourself with a thick marker.

- Record instructions. Use your phone to record your pharmacist explaining your meds. Play it back later.

- Don’t hide your struggle. Sixty-eight percent of people with low vision never tell their doctor they can’t read their labels. That’s dangerous. Tell someone. Your pharmacist, your family, your nurse. You’re not being difficult. You’re protecting your life.

Why This Isn’t Just a ‘Convenience’ Issue

Some people think this is about comfort. ‘Can’t you just ask your daughter?’ ‘Can’t you use a magnifying glass?’

No. This is a safety crisis. In 2022, a Guide Dogs UK survey found that 41% of people with low vision had taken expired medication. 58% couldn’t tell which bottle was which. 67% couldn’t read refill instructions. That’s not a mistake. That’s a system failure.

Dr. Tim Johnston from RNIB says it plainly: ‘The current system isn’t designed for people with sight loss. It’s a safety issue, not a convenience issue.’

And it’s getting worse. The population is aging. More people are on five, six, even ten medications. More people are losing vision or hearing. Yet regulations haven’t caught up. The FDA doesn’t require accessible labels. The UK’s MHRA says they’ll ‘look into it’-but hasn’t changed a rule yet.

Until there’s a law that says: ‘All prescription labels must be readable by people with low vision,’ this will keep happening. Until pharmacies are paid to do it right, they won’t.

What’s Changing-And What’s Not

There are glimmers of progress. The American Foundation for the Blind updated its labeling guidelines in 2021. The RNIB is rolling out a standardized labeling system in 2025. Some pharmacies are testing voice-activated dispensers.

But progress is slow. And uneven. A pharmacy in Toronto might have everything. One in rural Alabama might not even know what a talking pill box is.

The real change won’t come from apps or gadgets. It’ll come from policy. From funding. From training. From making accessibility a requirement-not an afterthought.

Until then, you’re not alone. But you’re still on your own. And that’s not fair.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I ask my pharmacist to label my pills in Braille?

Yes, you can ask. But Braille labels only help if you read Braille. Only about 15% of adults who lose vision later in life learned Braille, so it’s not a practical solution for most. It’s better to ask for large-print labels, high-contrast text, or audio instructions instead.

What if my pharmacy refuses to give me a large-print label?

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and similar laws in other countries, pharmacies must provide reasonable accommodations. If they refuse, ask to speak to the manager. If that doesn’t work, file a complaint with your state’s pharmacy board or consumer protection agency. You have the right to read your own prescriptions.

Are there free tools to help manage medications with low vision?

Yes. Use your smartphone’s built-in accessibility features. Turn on VoiceOver (iPhone) or TalkBack (Android). Use the camera to scan labels-it can read text aloud. Use free apps like Seeing AI or Microsoft Seeing AI to identify pills by taking a photo. You can also use a simple pill organizer with large print labels, which costs under $10.

How do I know if a pill is expired if I can’t read the date?

Ask your pharmacist to write the expiration date on the bottle with a permanent marker in large, bold letters. Or take a photo of the label with your phone and zoom in. Some apps can extract text from images. If you’re unsure, don’t take it. Return it to the pharmacy and ask for a new bottle with a clear date.

Can I get help from my doctor to set up a safe medication system?

Yes. Ask for a referral to an occupational therapist who specializes in low vision. They can help you set up a personalized system-labeling, organizing, using tools-and train you on how to use them. Many insurance plans cover this service. Don’t wait until you’ve made a mistake. Get help now.

patrick sui

December 2, 2025 AT 23:51