When you hear the word biosimilar, you might think it’s just a cheaper version of a brand-name drug-like a generic pill. But monoclonal antibody biosimilars aren’t like that at all. They’re not copies. They’re not duplicates. They’re highly similar, complex biological medicines built to match a reference product with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, effectiveness, or how your body responds. And they’re changing how cancer and autoimmune diseases are treated-especially in places where cost has been a barrier to life-saving care.

What Makes Monoclonal Antibody Biosimilars Different from Generics?

Think of a small-molecule generic drug like ibuprofen. It’s made of a single, simple chemical structure. Any factory can reproduce it exactly, down to the last atom. That’s why generics are cheap and easy to make.

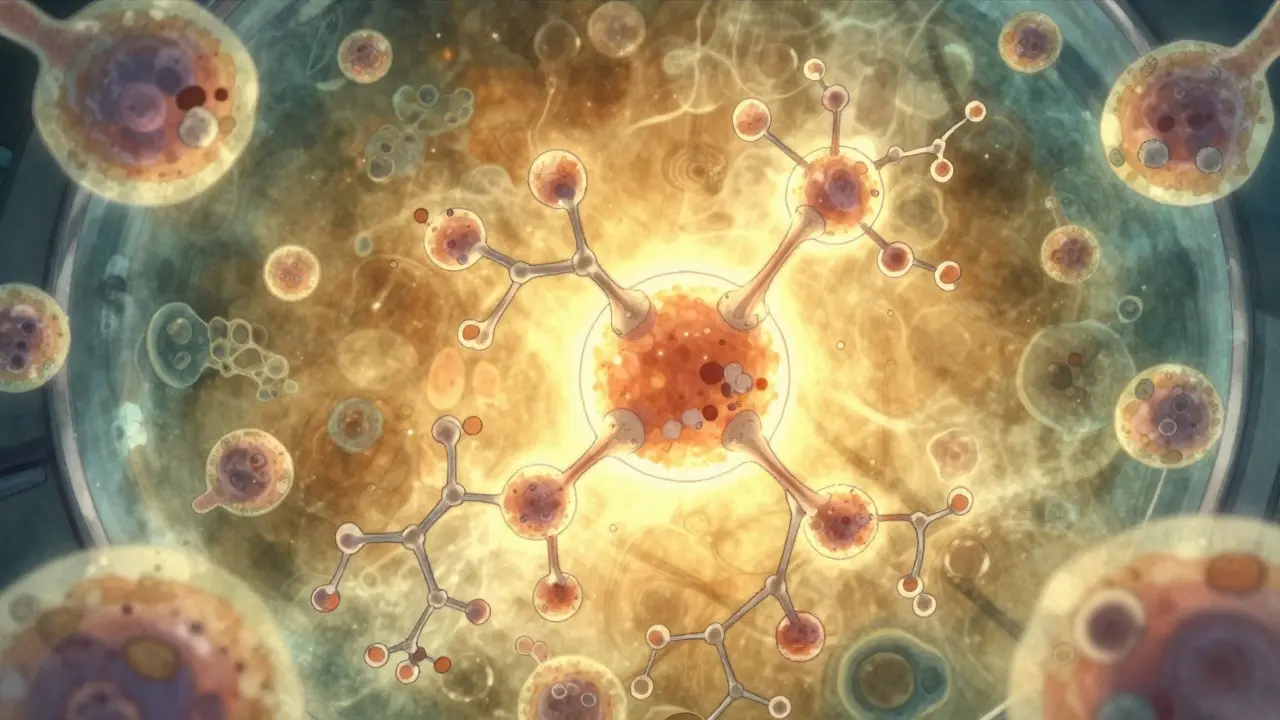

Monoclonal antibodies? They’re huge proteins-about 150,000 daltons in size. That’s more than six times heavier than insulin and nearly seven times heavier than growth hormone. They’re made by living cells-usually in bioreactors using genetically engineered Chinese hamster ovary cells. These cells don’t just spit out one identical molecule. They produce a family of slightly different versions, called variants. Tiny changes in sugar attachments (glycosylation), folding patterns, or charge can happen naturally during manufacturing. That’s why you can’t just copy the formula and expect the same result.

Regulators like the FDA and EMA don’t ask biosimilar makers to prove they’re identical. They ask them to prove they’re highly similar and that any differences don’t affect safety or how well the drug works. That means biosimilar developers must run hundreds of analytical tests, animal studies, and clinical trials to show their product matches the original in every way that matters to patients.

Approved Monoclonal Antibody Biosimilars and Their Uses

As of 2023, the FDA has approved over 20 monoclonal antibody biosimilars in the U.S. Here are the most commonly used ones and what they treat:

- Bevacizumab biosimilars (like Mvasi, Zirabev, Vegzelma): Used for colorectal, lung, ovarian, and brain cancers. These drugs block VEGF, a protein tumors need to grow blood vessels. Six biosimilars are now approved, and they’ve cut treatment costs by 30-50% in many hospitals.

- Rituximab biosimilars (Truxima, Ruxience, Riabni): Used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and rheumatoid arthritis. A 2022 study in JAMA Oncology tracked 1,247 patients switched from Rituxan to Truxima. No increase in side effects. No drop in response rates. But each treatment cycle saved 28% on average.

- Trastuzumab biosimilars (Ogivri, Herzuma, Kanjinti, Hercessi): Used for HER2-positive breast and stomach cancers. Six biosimilars are available in the U.S. They work the same way as Herceptin-attaching to the HER2 protein on cancer cells to stop growth and trigger immune destruction. Studies show no difference in survival or tumor shrinkage.

- Infliximab biosimilars (Remsima, Inflectra): Used for Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis. Remsima became the first monoclonal antibody biosimilar in the U.S. to get interchangeable status in July 2023. That means pharmacists can swap it for the brand without asking the doctor-just like with generics.

- Adalimumab biosimilars (Hyrimoz, Cyltezo, Amjevita): Used for the same autoimmune conditions as infliximab. Hyrimoz was approved in September 2023, and 14 more are in FDA review. Humira was the top-selling drug in the world for years-its biosimilars are expected to save the U.S. system over $100 billion by 2028.

These aren’t just numbers. They’re real options for patients who couldn’t afford treatment before. A woman with stage III breast cancer in rural Texas might now get trastuzumab biosimilar instead of skipping treatment entirely. A veteran with rheumatoid arthritis might finally get off opioids because his insurance now covers a biosimilar infliximab.

How Do We Know They’re Safe?

One big fear is immunogenicity-your immune system reacting to the drug as if it’s a foreign invader. This can cause allergic reactions, reduced effectiveness, or even serious side effects.

There was a case with cetuximab (a different monoclonal antibody) where some patients had severe allergic reactions because of a sugar structure called alpha-1,3-galactose. It turned out this sugar was present in the original drug too-so the issue wasn’t the biosimilar. It was the molecule itself. That’s why regulators require biosimilar makers to test for these exact same risks.

The EMA tracked 1.2 million patient-years of exposure to monoclonal antibody biosimilars between 2013 and 2021. Only 12 unexpected immune reactions were reported. That’s a rate of 0.001%-the same as the reference products. The FDA has approved every biosimilar only after reviewing clinical trial data from thousands of patients. No major safety signals have emerged that weren’t already known from the original drug.

Post-marketing surveillance is ongoing. Hospitals track every patient who gets a biosimilar. If a new pattern shows up-say, more cases of infusion reactions in a certain group-regulators are notified immediately. So far, the safety profile matches the original.

Cost Savings and Market Impact

Monoclonal antibodies are expensive. The original versions often cost $10,000 to $20,000 per year per patient. With biosimilars, prices drop by 30-70% depending on competition and market rules.

According to Evaluate Pharma, biosimilar monoclonal antibodies will save the U.S. healthcare system $250 billion between 2023 and 2028. Bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and rituximab biosimilars will account for 78% of those savings.

By 2027, IQVIA predicts monoclonal antibody biosimilars will make up 35% of all biologic prescriptions in the U.S.-up from 18% in 2022. That’s a 21.7% annual growth rate. Cancer therapies will drive most of that growth, making up 62% of biosimilar use.

But savings aren’t automatic. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) still control which drugs get covered. In 32% of cases, biosimilars aren’t included in formularies because of contracts with brand manufacturers. Some hospitals still default to the original drug because of inertia or lack of provider education.

Barriers to Wider Use

Even with proven safety and savings, adoption is slower than it should be.

First, there’s patent litigation. A 2023 study from UC Hastings found that each monoclonal antibody biosimilar faces an average of 14.7 patent challenges. These lawsuits delay market entry by years. Sometimes, the original manufacturer buys off the biosimilar maker to keep it off the market.

Second, many doctors aren’t confident prescribing them. A 2022 ASCO survey showed only 58% of oncologists felt “very confident” in switching patients to biosimilars. That’s not because of safety concerns-it’s because they weren’t trained on them. Medical schools still teach mostly about brand-name drugs.

Third, patients are confused. They hear “biosimilar” and think “inferior.” Education campaigns are improving, but misinformation still spreads. A patient might refuse a biosimilar because their neighbor heard it “didn’t work.”

What’s Next?

The pipeline is full. As of September 2023, the FDA had 37 monoclonal antibody biosimilars in review. Six are targeting pembrolizumab (Keytruda), a leading immunotherapy for melanoma and lung cancer. If approved, these could cut costs by more than 50% for a drug that currently costs over $150,000 a year.

The EMA is also preparing new guidelines for even more complex biosimilars-like bispecific antibodies (which target two different proteins at once) and antibody-drug conjugates (which carry chemotherapy directly to cancer cells). These are the next frontier.

Technology is helping too. New mass spectrometry tools can now detect differences in protein structures at the level of single sugar molecules. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance recommends 127 specific analytical tests to prove biosimilarity. That’s not overkill-it’s necessary. These drugs are too important to get wrong.

Final Thoughts

Monoclonal antibody biosimilars aren’t a compromise. They’re a breakthrough. They bring life-saving treatments to people who couldn’t afford them. They don’t cut corners-they meet higher standards. They’re not generics. They’re something better: scientifically rigorous, clinically proven, and economically essential.

For patients with cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, or Crohn’s disease, biosimilars mean more treatment options. More access. More time. More hope. And that’s not just good for the system. It’s good for people.

Are monoclonal antibody biosimilars safe?

Yes. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require extensive testing before approval. Biosimilars must show no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or effectiveness compared to the original drug. Post-marketing data from over a million patient-years shows safety profiles are equivalent. Rare immune reactions occur at the same low rate as with the reference product.

Can biosimilars be substituted for the original drug without a doctor’s permission?

Only if the biosimilar is designated as "interchangeable" by the FDA. As of 2023, only Remsima (infliximab) has received this status in the U.S. Interchangeable biosimilars can be swapped at the pharmacy level without prescriber involvement, just like generic pills. Most biosimilars still require a new prescription if switching from the reference product.

Why are biosimilars cheaper than the original drugs?

Biosimilars don’t require the same massive clinical trials as the original drug. The manufacturer doesn’t need to prove safety and effectiveness from scratch-they only need to show similarity. This cuts development costs by 60-70%. Competition among multiple biosimilar makers also drives prices down. However, manufacturing is still complex and expensive, so savings are typically 30-70%, not 90% like with small-molecule generics.

Do biosimilars work as well as the original monoclonal antibodies?

Yes. Clinical trials and real-world studies show no difference in effectiveness. For example, studies switching patients from Rituxan to Truxima found identical response rates in lymphoma and no increase in side effects. The same holds true for trastuzumab in breast cancer and bevacizumab in colorectal cancer. Regulatory agencies only approve biosimilars after confirming equivalent outcomes.

How many monoclonal antibody biosimilars are approved in the U.S.?

As of 2023, the FDA has approved over 20 monoclonal antibody biosimilars. Key ones include biosimilars for bevacizumab (6 approved), rituximab (3), trastuzumab (6), infliximab (2), adalimumab (5), and others. More are in review, especially for newer drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab.

Katelyn Slack

January 5, 2026 AT 23:49