When a generic drug company challenges a brand-name drug’s patent and wins, it gets a 180-day window to sell its version with no competition. That’s the 180-day exclusivity rule under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Sounds fair, right? But here’s the catch: the brand-name company can still launch its own generic version - called an authorized generic - during that same 180 days. And when they do, the first generic company’s profits can crash by half.

How the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule Was Supposed to Work

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was meant to balance two things: letting brand-name drug makers protect their patents, and letting generic companies get to market fast. The 180-day exclusivity was the incentive. If a generic company filed a Paragraph IV certification - basically saying, "This patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it" - and won in court or forced a settlement, they got exclusive rights to sell the generic for six months. No other generic could enter. The idea was simple: reward the company that took the legal risk.The math was clear. A single blockbuster drug could bring in billions. The first generic to enter could capture 80% of the market. That meant tens or even hundreds of millions in profit. For smaller generic manufacturers, this was their shot at becoming big. The law assumed the brand-name company would sit back and wait. But that’s not what happened.

What Are Authorized Generics, and Why Do They Break the System?

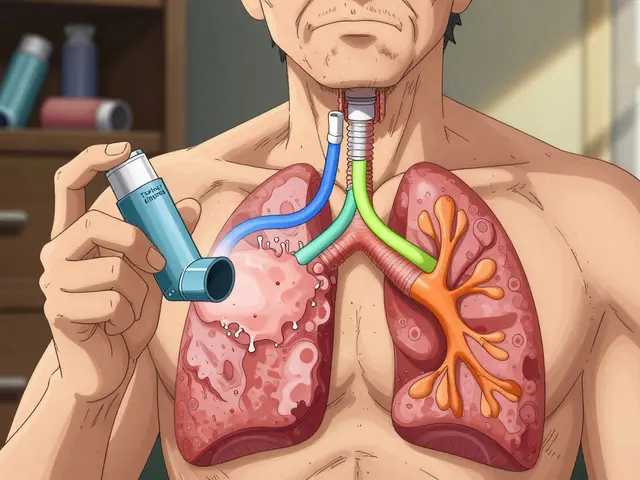

An authorized generic isn’t a copy. It’s the exact same drug, made by the brand-name company, sold under a different label. No extra testing. No FDA review. Just a new box and a lower price. And because it’s the same product, pharmacies and insurers don’t care which one they buy. They just want the cheapest option.Between 2005 and 2015, brand-name companies launched authorized generics in about 60% of cases where the 180-day exclusivity was granted. When that happens, the first generic’s market share drops from 80% to around 50%. Revenue falls by 30-50%. In one case, Teva Pharmaceuticals estimated it lost $287 million because Eli Lilly launched an authorized generic of Humalog during Teva’s exclusivity period.

This isn’t just bad luck. It’s a strategy. Brand-name companies know the exclusivity rule. They know the timing. They’ve got the manufacturing lines ready. And they use that knowledge to split the market before the generic even gets started.

The Legal Gray Zone

Here’s the problem: the law doesn’t say brand-name companies can’t do this. The Hatch-Waxman Act only blocks other generic companies from entering. It doesn’t stop the original maker from selling their own version. That’s not illegal. It’s just not what Congress had in mind.That’s why lawsuits keep popping up. The Federal Trade Commission has filed 15 antitrust cases since 2010 against brand-name companies accused of using authorized generics to delay real competition. Some of those cases allege that the brand and generic companies secretly agreed: "You get exclusivity, we’ll launch our version right after you - but we’ll split the profits."

These deals are called "pay-for-delay" settlements. They’re not always illegal - courts have ruled some are okay - but they’re murky. The FTC says they hurt consumers. Generic companies say they’re forced into them just to survive.

Who Pays the Price?

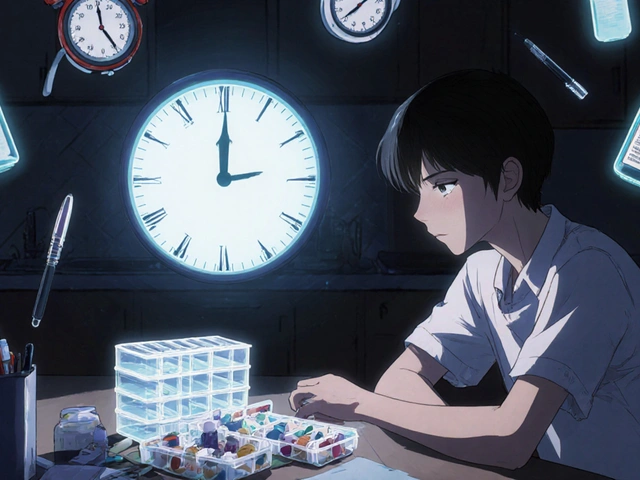

At first glance, prices drop when authorized generics enter. A 2021 RAND study found prices fell 15-25% when an authorized generic competed with the first generic. That sounds good for patients. But look closer.When the first generic company loses money, it can’t afford to challenge the next patent. Smaller generic manufacturers - the ones without deep pockets - are walking away from Paragraph IV challenges altogether. Drug Patent Watch found that 78% of first applicants now negotiate contracts with brand-name companies just to delay the authorized generic launch. That means fewer patent challenges. Fewer generics. Fewer price drops down the line.

The result? A system that’s supposed to drive down drug costs is slowly choking off competition. The 180-day exclusivity was meant to be a spark. Now it’s often just a flicker.

What’s Being Done About It?

Congress has tried to fix this. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been reintroduced multiple times since 2009. It would ban brand-name companies from launching authorized generics during the 180-day window. The FDA’s Commissioner Robert Califf told Congress in 2023 he supports this change. The FTC agrees - they estimate that blocking authorized generics during exclusivity would boost first generic revenues by 35% on average.But the brand-name industry pushes back. They say authorized generics help patients right away. They point to lower prices and more options. And they’re not wrong - in the short term, prices do drop faster. But the long-term cost? Fewer challengers. Fewer generics overall. And eventually, higher prices again.

Real-World Impact: The Numbers Don’t Lie

- Between 2015 and 2020, first generic companies captured only 52% of the revenue they were theoretically entitled to, thanks to authorized generics. - Generic drug manufacturers spend an average of $3.2 million just to file a Paragraph IV challenge. - About 28% of first applicants lose part or all of their exclusivity due to mistakes in timing or paperwork. - In 2022, 78% of new generic approvals involved a patent challenge - up from 45% in 2000. But the number of successful challenges has stalled because the risk is too high.Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz have teams of lawyers, regulatory experts, and commercial strategists working just to protect their exclusivity window. They hire consultants for $500,000-$1 million just to make sure they trigger the clock correctly. One misstep - shipping the product a day too early or too late - and they lose everything.

What This Means for the Future

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed for a simpler time. Back then, drug patents were clearer. Generic companies were smaller. Brand-name manufacturers didn’t have the infrastructure to launch their own generics overnight.Now? It’s a game of chess played with billions on the board. The authorized generic loophole has turned the 180-day exclusivity from a reward into a trap. It’s not that the law is broken. It’s that the rules were never meant to account for this kind of maneuver.

Unless Congress steps in, we’ll keep seeing the same pattern: a generic company wins the legal battle, only to watch the brand-name company walk onto the field with the same jersey. The patient gets a cheaper pill - but the system gets weaker.

For now, the only winners are the big players who can afford to play both sides. The rest - smaller generics, patients waiting for the next breakthrough drug, and even the FDA - are left trying to clean up the mess.

Can a brand-name company legally launch an authorized generic during the 180-day exclusivity period?

Yes. The Hatch-Waxman Act only prevents other generic manufacturers from entering the market during the 180-day window. It does not prohibit the original brand-name company from selling its own drug under a different label. This is a legal loophole that has been exploited since the 1980s.

Why don’t generic companies just sue the brand for launching an authorized generic?

They can’t - because it’s not illegal. Courts have consistently ruled that selling an authorized generic is not anticompetitive under current law. The only recourse is to negotiate a settlement before filing a patent challenge, or push for legislative change. Some generic companies now include clauses in settlement agreements that block the brand from launching an authorized generic.

How does the FDA define "first commercial marketing" to trigger the 180-day clock?

The FDA says it begins when the generic drug is both approved and actually shipped to customers. Just getting approval isn’t enough. The product must be in the hands of distributors or pharmacies. Many companies lose exclusivity because they ship too early (before final approval) or too late (after competitors enter the market).

Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

No. Regular generics are made by different companies and must prove bioequivalence through the ANDA process. Authorized generics are made by the original brand-name company, using the same facility and formula, just sold without the brand name. They are identical in every way - including inactive ingredients - to the branded version.

What’s the difference between a Paragraph IV certification and a Paragraph III certification?

A Paragraph III certification means the generic applicant agrees to wait until the patent expires before selling their drug. A Paragraph IV certification is a legal challenge - the applicant claims the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. Only Paragraph IV filers qualify for the 180-day exclusivity. This is the only path to the financial reward - and the only path that triggers patent litigation.

Can multiple generic companies share the 180-day exclusivity?

Yes, under the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act. If two or more companies file substantially complete ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, they can share the exclusivity period. But if one of them doesn’t launch within 75 days of approval, they lose their share. This rule was meant to prevent delays, but it’s rarely used because companies usually stagger their filings to avoid sharing.

Is there a trend toward fewer Paragraph IV challenges because of authorized generics?

Yes. Since 2015, the number of Paragraph IV challenges has plateaued despite more drugs losing patent protection. Smaller generic companies are walking away because the cost of litigation ($2-5 million) isn’t worth the risk when the brand can undercut them with an authorized generic. Only large generics with deep pockets or settlement deals still pursue these challenges.

What Should Generic Companies Do Now?

If you’re a generic manufacturer thinking about filing a Paragraph IV challenge, here’s what you need to do:- Run a full patent landscape analysis - know every patent, every extension, every possible settlement angle.

- Build a financial model that assumes a 50% revenue loss from an authorized generic.

- Negotiate a no-authorized-generic clause into any settlement agreement - even if it means accepting a smaller payout.

- Set up a cross-functional team (legal, regulatory, commercial) at least six months before approval.

- Track the FDA’s guidance on triggering exclusivity - don’t guess, follow the rules exactly.

There’s no magic fix. The system is broken. But if you understand the risks, you can still win - just not the way the law originally intended.

Ian Ring

January 5, 2026 AT 01:38