Respiratory Risk Calculator

Based on CDC data and 2018 research showing synergistic respiratory depression effects.

Calculate Your Risk

Combined Respiratory Depression Risk

According to CDC data, this combination increases respiratory depression risk by up to 10x compared to opioids alone.

Important: This calculation uses simplified medical modeling based on 2018 study data showing 78% ventilation reduction when fentanyl and midazolam are combined. Actual risk depends on individual physiology, tolerance, and other factors.

The CDC reports that 22.5% of deaths involving illicit opioids also contained benzodiazepines.

When you take opioids for pain and benzodiazepines for anxiety, you might think you’re just managing two separate problems. But together, these drugs can shut down your breathing-quietly, dangerously, and sometimes fatally. This isn’t a rare accident. It’s a predictable, well-documented public health crisis that’s killed thousands in the last decade.

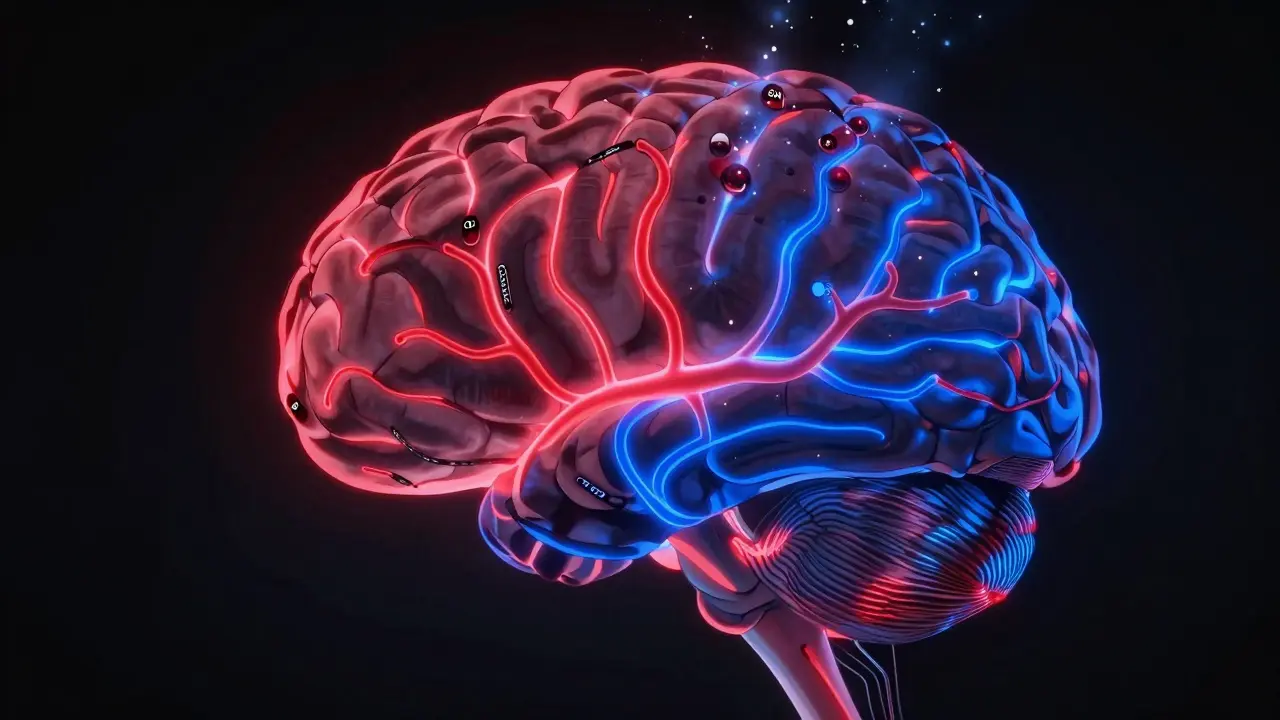

Why This Combination Kills

Opioids like oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl slow breathing by targeting specific brainstem neurons. They hit the mu-opioid receptors in areas like the preBötzinger Complex and the Kölliker-Fuse/Parabrachial complex, which control the rhythm and depth of breath. The result? Longer exhales, fewer breaths per minute, and eventually, no breath at all. Benzodiazepines-drugs like diazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam-work differently but with the same deadly outcome. They boost GABA, the brain’s main calming chemical. This over-inhibits the nervous system, including the parts that keep you breathing. Alone, a normal dose might make you drowsy. But when mixed with opioids, the effect isn’t just added-it’s multiplied. A 2018 study showed that when fentanyl and midazolam were given together, minute ventilation dropped by 78%. Alone, fentanyl cut it by 45%. Midazolam alone? Just 28%. That’s not coincidence. It’s synergy. The brain’s breathing control system gets hit from two sides at once, and it can’t compensate.The Numbers Don’t Lie

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that in 2019, benzodiazepines were present in 16% of all opioid overdose deaths. For deaths involving illicit opioids like heroin or fentanyl, that number jumped to 22.5%. By 2020, about 17% of opioid-related fatalities still involved benzodiazepines. That’s one in six people who died from an opioid overdose also had a benzodiazepine in their system. People prescribed both drugs have a 10 times higher risk of dying from an overdose than those taking opioids alone. The highest rates are among those aged 45 to 64-people often managing chronic pain and anxiety, sometimes for years. They’re not users. They’re patients. And they’re being put at extreme risk by a system that still allows this combination to be written.How the Brain Stops Breathing

Research from 2021 using mice models showed that opioids don’t just slow breathing-they break the rhythm. They silence neurons in the preBötzinger Complex, the brain’s natural pacemaker for inspiration. At the same time, they over-activate the Kölliker-Fuse region, forcing longer, deeper exhales. This creates a pattern of gasping breaths followed by long pauses. In humans, this looks like shallow, irregular breathing before complete stoppage. Benzodiazepines make this worse by suppressing the entire respiratory network. They don’t just affect one area-they mute the whole system. The result? The brain can’t trigger a breath even when oxygen levels drop dangerously low. The body loses its ability to auto-correct. This is why naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug, doesn’t work fully here. It reverses the opioid part-but leaves the benzodiazepine-induced suppression untouched.

Doctors Still Prescribe This

Despite warnings from the FDA since 2016-complete with a black box warning labeling this combination as life-threatening-doctors still write these prescriptions. In 2022, 8.7% of patients on long-term opioid therapy were still being given benzodiazepines. That’s nearly one in ten. Why? Sometimes it’s ignorance. Sometimes it’s pressure. Patients with chronic pain often have anxiety, insomnia, or panic attacks. Prescribers reach for benzodiazepines because they’re fast, familiar, and seem to help. But they don’t see the hidden cost. The American Society of Anesthesiologists says this combination should be avoided whenever possible. The CDC’s 2016 guidelines say the same. Yet, many providers still think, “I’ll just give a low dose.” But there’s no safe low dose when these two drugs are combined. The risk isn’t linear-it’s exponential.What Can Be Done Instead

There are safer alternatives for both pain and anxiety. For anxiety, SSRIs like sertraline or escitalopram work over time with far less risk. Buspirone is another non-addictive option. For insomnia, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-I) is more effective long-term than benzodiazepines. For pain, non-opioid options like gabapentin, physical therapy, acupuncture, or even certain antidepressants like duloxetine can help. In many cases, reducing or eliminating opioids altogether leads to better outcomes-not just for breathing, but for mood, sleep, and function. If a patient truly needs both medications-for example, someone with severe epilepsy and chronic pain-the dose should be kept as low as possible, monitored weekly, and reviewed every 30 days. No long-term prescriptions. No refills without reevaluation. No assumptions.

Kegan Powell

January 26, 2026 AT 16:55