Why dissolution testing matters more than you think

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA know it will? The answer isn’t in clinical trials on thousands of patients. It’s in a lab, with a rotating basket, a beaker of buffered liquid, and a machine measuring how fast the drug dissolves. This is dissolution testing - and it’s the invisible gatekeeper of generic drug quality.

For every generic drug approved in the U.S., the FDA doesn’t require new human studies to prove it works. Instead, they demand proof that the drug releases its active ingredient at the same rate and amount as the original. That’s where dissolution testing comes in. It’s not just a formality. It’s the primary tool the FDA uses to guarantee that a $5 generic tablet delivers the same effect as its $50 brand-name counterpart.

How dissolution testing actually works

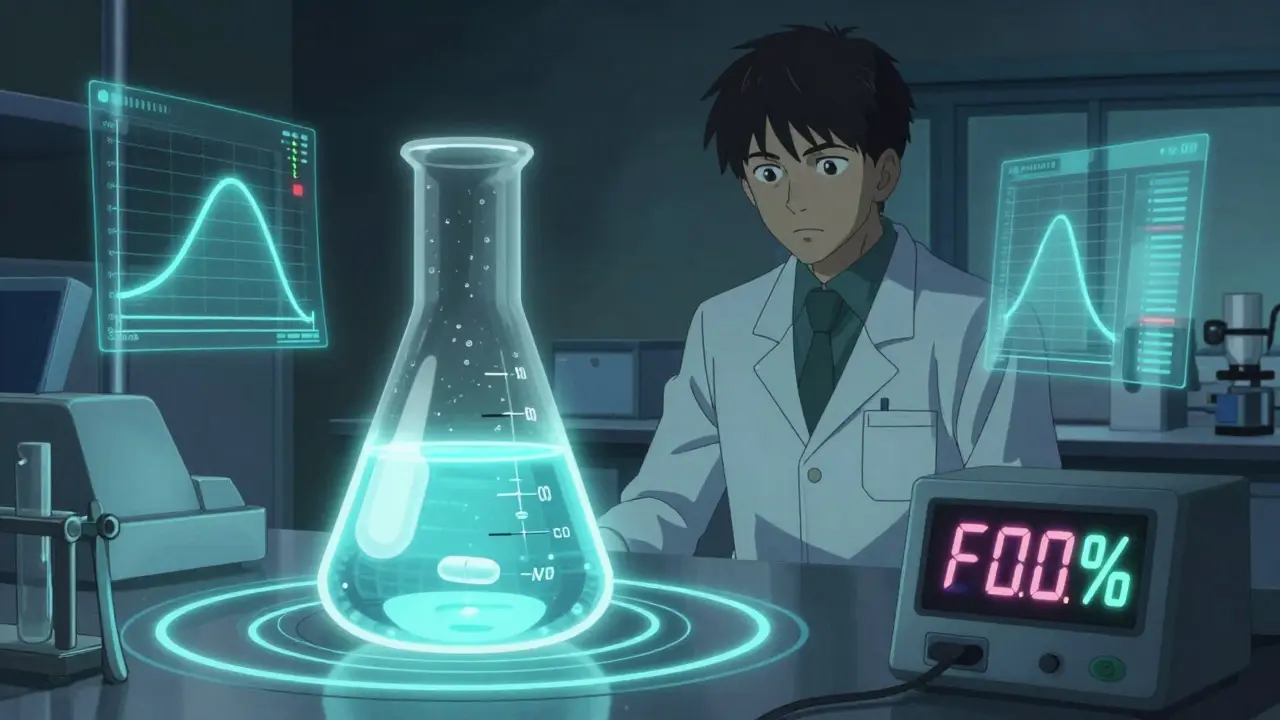

The process sounds simple: put a pill in a liquid that mimics stomach fluid, stir it, and measure how much drug comes out over time. But the details are anything but simple. The FDA requires manufacturers to follow strict conditions - the exact type of machine (usually USP Apparatus 1 or 2), the rotation speed (often 50 to 100 rpm), the volume of liquid (500 to 900 mL), the pH level (which changes depending on the drug), and the exact times when samples are taken.

For immediate-release tablets - the most common type - the standard rule is that at least 80% of the active ingredient must dissolve within 45 minutes. But that’s not a one-size-fits-all number. For highly soluble drugs (BCS Class I), the FDA allows a single-point test: just check at 30 minutes using 900 mL of 0.1N HCl. For drugs that release slowly, like extended-release painkillers, the test runs for hours and includes multiple pH levels and even alcohol challenges to simulate what happens if someone takes the pill with a drink.

It’s not enough to just dissolve. The method must be able to tell the difference between a good formulation and a bad one. If two pills look identical but one releases the drug too fast or too slow, the test must catch it. That’s called discriminatory power - and it’s why developing a valid dissolution method can take 6 to 12 months for complex drugs.

The role of the f2 similarity factor

Comparing two dissolution profiles isn’t about matching curves perfectly. It’s about proving they’re statistically similar. That’s where the f2 factor comes in. It’s a mathematical score between 0 and 100. If the f2 value is 50 or higher, the FDA considers the two products equivalent in how they release the drug.

Think of it like this: if the brand-name drug releases 70% of its drug at 15 minutes, 85% at 30 minutes, and 95% at 45 minutes, the generic must follow almost the exact same path. A curve that spikes too early or lags too far behind gets flagged - even if the total amount released is the same. Why? Because timing matters. A drug that releases too fast might cause side effects. One that releases too slow might not work at all.

This isn’t guesswork. The FDA uses this method to approve over 90% of generic drugs without requiring human bioequivalence studies. That saves time, money, and avoids putting patients through unnecessary testing.

When the FDA says ‘no human study needed’

Here’s the big win for generic drug makers: if a drug meets certain criteria, the FDA will waive the need for a full human bioequivalence study. That’s only possible because dissolution testing is so reliable.

Drugs classified as BCS Class I - meaning they’re highly soluble and highly absorbable - are prime candidates for this shortcut. For these, if the generic matches the reference product’s dissolution profile under standardized conditions, the FDA accepts that as proof of bioequivalence. That’s why drugs like aspirin, metformin, and atorvastatin generics are approved so quickly.

Even more surprising: the FDA is considering extending this waiver to BCS Class III drugs (highly soluble but poorly absorbed). If approved, this could cut development time for dozens of new generics by months or even years.

But this only works if the dissolution method is scientifically sound. That’s why the FDA maintains the Dissolution Methods Database - a public library of approved test methods for over 2,800 drug products. Manufacturers don’t have to reinvent the wheel. They can use a proven method, validate it, and submit it with their application.

What happens when things go wrong

Not every generic gets approved on the first try. Sometimes, a company’s dissolution data looks good on paper but doesn’t match the reference product closely enough. In those cases, the FDA may ask for more data - extra time points, different pH conditions, or even a human bioequivalence study.

There are also cases where a generic product performs well in human trials but fails the dissolution test. The FDA can still approve it - but only if the manufacturer proves the difference doesn’t affect safety or effectiveness. This is rare, but it happens. It shows the FDA doesn’t treat dissolution testing as a rigid rulebook. It’s a tool, and they use it flexibly, based on science.

Manufacturers also face strict rules when they change anything about the product - the factory, the supplier of the active ingredient, or even the shape of the tablet. Under the SUPAC-IR guidelines, they must prove the dissolution profile hasn’t changed. If it has, they need FDA approval before selling the new version.

Why this system works - and why it’s changing

The FDA’s approach to dissolution testing isn’t just about control. It’s about efficiency. By using in vitro tests to predict in vivo performance, they avoid running hundreds of expensive, slow, and ethically complex human trials. It’s a smarter way to get safe, affordable drugs to patients faster.

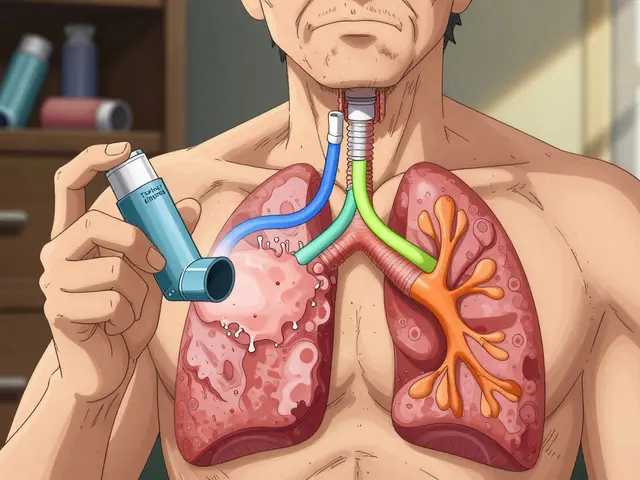

But it’s not perfect. For low-solubility drugs - like many newer cancer treatments - dissolution testing is harder. These drugs don’t dissolve easily, and their release can be affected by food, stomach pH, or even gut bacteria. That’s why the FDA is pushing for more physiologically relevant methods - tests that mimic real human digestion, not just lab conditions.

By 2025, experts predict that 35% of generic approvals will rely on standardized dissolution methods, up from 25% in 2020. That growth isn’t accidental. It’s the result of years of refining what works and discarding what doesn’t.

At its core, dissolution testing is about trust. It’s the FDA saying: ‘We don’t need to test this on people again because we’ve proven, scientifically, that it behaves the same way.’ That’s powerful. And it’s why millions of people can safely take generic drugs every day - knowing they’ll get the same results as the brand name.

What you should know as a patient

You don’t need to understand the math behind f2 values or the specs of USP Apparatus 2. But you should know this: every generic drug you take has passed a rigorous, science-based test to prove it works like the original. The FDA doesn’t approve generics because they’re cheaper. They approve them because they’ve been proven to be the same.

If your doctor switches you from a brand to a generic, you can trust that change. The system is designed to protect you - not to cut corners. And when the FDA says a drug is bioequivalent, it’s not a marketing claim. It’s a laboratory fact, backed by data you can’t see but can rely on.

clarissa sulio

February 2, 2026 AT 23:36